Jerusalem Tunnel

Time-travel adventure: an American boy helps a young Jewish survivor of a Roman massacre fulfill an important task and gives him hope for the future. Ages 9-14.

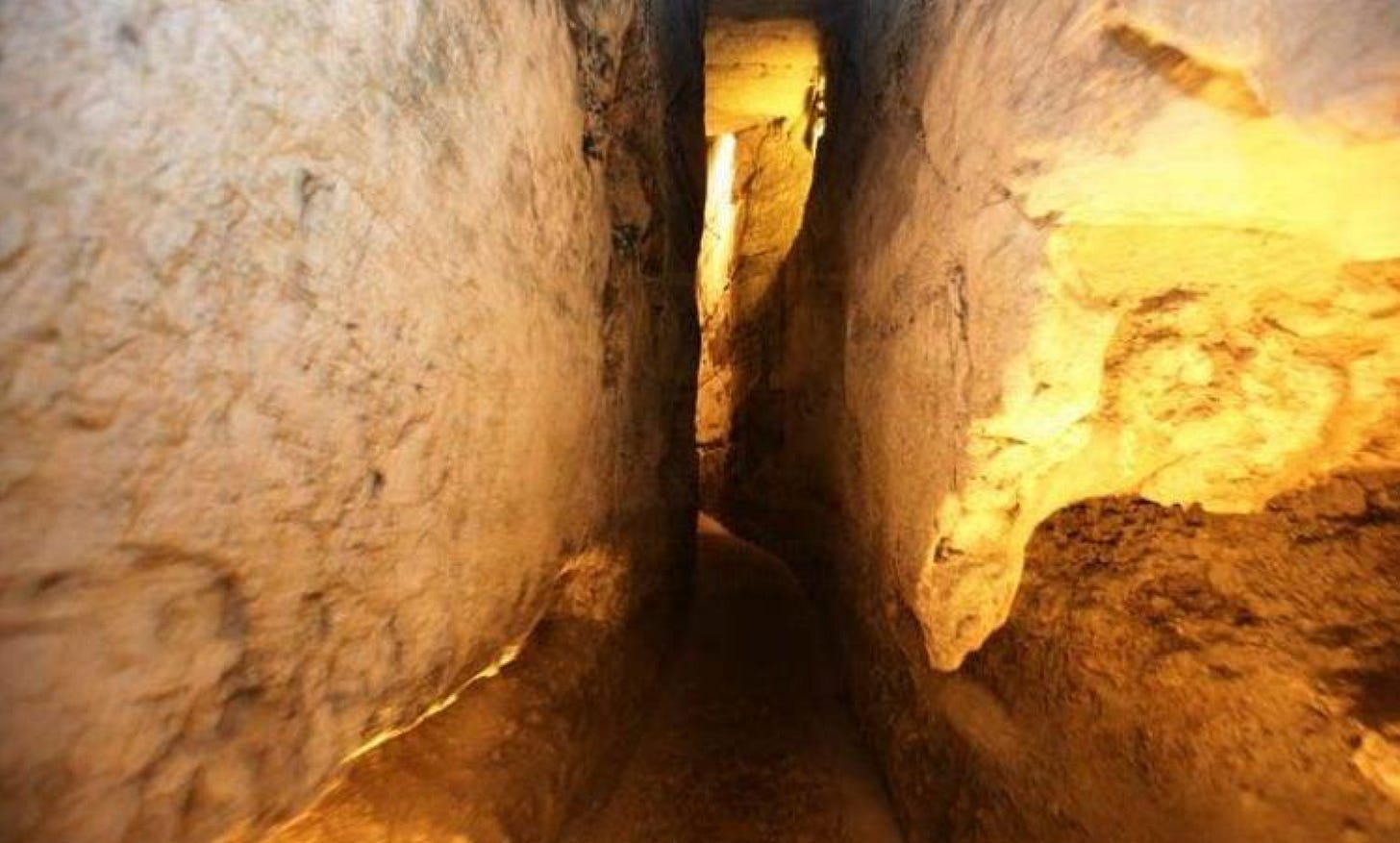

Hunched in his sweatshirt, Dan slowed down, letting the tourists in front of him disappear beyond a turn. “It’s my thirteenth birthday,” he muttered, “and I’m stuck on this miserable archaeological tour in this cold, damp tunnel.” He’d wanted to stay home and have a blowout Bar Mitzvah bash, like his friends. But his folks had brought him to Jerusalem. Now he was spending his birthday traipsing through a dim, narrow, boring tunnel beneath the city.

His folks were so excited about visiting the ancient sites that they had borrowed every book the library had on Israeli archaeology. Mom had even started a needlepoint of an ancient Israeli coin, which she worked on every free moment. Neither cared that Dan wasn’t interested in archaeology. Neither cared that he was missing the biggest basketball game of the season, or that without him his team didn’t have a chance. It’s my Bar Mitzvah, he thought, kicking a stone viciously. And I’m dragged around like a dog on a leash.

“Hurry up!” The stout man behind Dan poked his shoulder. Dan turned and glared. The man and his wife had been trying to pass Dan ever since the tour began, but the tunnel was narrow and both the man and his wife were very fat. Up ahead, Dan saw a little alcove. He stepped into it so that the couple could pass.

As Dan pressed his back against the uneven stones, a cold wind ruffled his jeans. Wind in a stone tunnel? Dan crouched to investigate. A large block of stone was set slightly back from the others, leaving a slot through which came a riffle of dank air. The wind also carried voices, and with a shock he realized they were his parents’. He heard his mother say, “…uncooperative.” His father replied with “…selfish…lazy.” Then he heard his own name. They were talking about him.

He jumped to his feet, his hands in such tight fists that his nails dug into his palms. Uncooperative, when you made me have my Bar Mitzvah here instead of at home with my buddies? Selfish, after you forced me to miss the big game? Lazy, because I wanted to skip this stupid tour?

Enraged, he kicked the wall. But instead of receiving a satisfying impact that would have jarred him back to reality, his foot continued forward. The rock slid out of the way as though it were greased. Dan was thrown off balance, stumbling toward the wall. He threw out his hands and caught himself, his head just inches from the stones.

The impact sent shock waves from the palms of his hands clear to his feet. He struggled to catch is breath. Then he felt something digging into his hand—something metal. It was a small coin, wedged between the stones. He wiggled it loose and studied it. One one side was a wine goblet with strange writing over it. On the other side, the writing encircled three pomegranates on a single stem. With a shock he realized that he was holding the model for his mom’s needlepoint. How had it gotten into the crack? He rubbed the blackened coin. The mystery of the past rose about him enveloping him with questions. Who had carried this coin. When was it used? How did it get stuck between two stones in the tunnel wall?

As he turned the coin over and over, he shivered. The draft was much stronger now. Crouching down, he studied the place he’d kicked. The rough stone had slid through the wall a foot or two. The dimly lit opening contrasted with the alcove where he stood, which was lit brightly by an electric light.

If I explore this secret tunnel, the light will guide me back, he thought. My Bar Mitzvah adventure. Maybe I’ll find the lost Ark of the Covenant, like in that old Harrison Ford movie. It would make up for the rest of this miserable trip. He straightened, looking up and down the tourist tunnel. No one was in sight. He crouched down and scrambled through the opening.

The new tunnel was so low that he had to crawl. The cold wind blowing against his face chilled him, but a faint light drew him forward. The tunnel ended suddenly, leaving Dan in a spacious cavern. He stood up and dusted off his knees. Mist swirled. The slow, irregular drip-drip of water beat a counterpoint to his pounding heart. This is crazy, he thought. I should go back.

He turned toward the tunnel. Its opening shone like a beacon. But something pulled him toward the darkness. He thrust his hands into his pockets and hunched his shoulders against the damp. His fingers wrapped around the coin. Heads I stay, tails I go.

The coin gleamed eerily in the dim light, three pomegranates on their stem. He rubbed the pomegranates, then tossed and caught the coin.

Suddenly he coughed. Smoke wafted through the hot, sunny plaza. A wail broke the stillness, and a crowd surged past, chased by two toga-clad soldiers with outstretched spears. Just as suddenly the plaza was empty.

I’m on a stage, Dan thought. A play, like that Julius Caesar we saw in school last year. But all he could see was an alley to the left, another to the right, and between them, the plaza. His fingertips brushed the warm stones and rustled some dry weeds that had survived briefly in a crevice in the wall. A small, dusty brown lizard, the length of his finger, scurried across the stones, then squirmed between the wall and a wooden door, disappearing from view.

A door. For the first time Dan noticed that the plaza was lined with arches. Some were sealed with wooden doors and heavy locks, others were boarded and fastened shut. As he turned and stared at the plaza, he heard shouts and the sound of feet. More soldiers? I’ve got to get out of here!

Dan looked for the opening through which he had come, but it was gone. In its place was an arch with a partly open wooden door. Pushing the door wider, he stepped into a dark hallway, then shut the heavy wooden door behind him.

Saying a quick prayer of thanksgiving for the silent soles of his sneakers, he crept toward the passage. After a few steps it opened into a small courtyard, where smoky sunlight filtered through the branches of a dying pomegranate tree. Across the courtyard was an open door. He started toward it, then stopped as a faint movement caught his eye. A rat? He took three steps toward some bushes. A branch moved, pushed aside by small, dirty fingers. A child.

Dan crouched down. “You can come out,” he whispered. “I won’t hurt you.”

The bush rustled, and a small boy, perhaps seven years old, peeked out. “You’re not a Roman soldier. Who are you?” demanded the boy.

“I’m Dan. I…” Dan stopped. “Is this a play?” He hoped it was. But he knew it wasn’t.

“A play?” The child crept out from behind the bush, staring at Dan with a pitying look. “Did the Romans hit you on the head? Shabano was confused for three days after the Romans hit him.”

“Who’s Shabano?”

“He’s …he was my brother.” The child wiped his eyes with a dirty fist. “The Romans killed him, just like they killed Imma, Shifra, and Leah. But they didn’t kill me. I hid.”

Dan wiped his sweating hands on his jeans and swallowed. Where was he? More important, when was he? And who were those icy-eyed soldiers? “W-w-w-why did the soldiers kill them?”

The child stamped his foot impatiently. “Because they want Jerusalem, silly! Because they want all the Jews dead. Because …” His face crumpled, and tears truckled down his thin cheeks. “Abba says they are angry because we don’t want to be like them. They think they’re so great, with their stone statues that they think are gods. They want us to bow to their stupid statues, their idols. Abba says we can’t win. The Romans are too many and too well trained. And they like killing people. Jews hate to kill. So we get killed instead. Imma!” The child crossed his arms over his face and began sobbing. Dan drew the child to him, holding him as he sobbed.

Finally the child hiccupped and lifted his head. “Will you help me?”

Panic filled Dan. I want to go home! I don’t know anything about this place. How can I help? But the child’s huge, sad eyes begged Dan to stay. Dan swallowed hard. “Let’s go look for your…” Dan stopped. Mother, he was about to say. But she was dead.

“Where’s your father?”

The child hugged his skinny arms to his chest, rubbing his bare foot in the dust. He sniffed and looked at Dan, his eyes dark pools in his thin face. “He was at the Temple. He worked there.”

Past tense, thought Dan. “He’s dead too?”

The child nodded. “Shabano said the Romans killed everyone at the Temple early this morning. Now they are destroying the Temple. He said that’s what’s burning. And when the earth shakes, it’s not an earthquake. It’s the wall of the Temple, falling.”

As if echoing the boy, a huge, dull boom resounded in the distance, and the earth trembled.

The Temple. Dan stepped backward. Yesterday, when touring the southern part of the Temple wall, the guide had pointed out huge, toppled stones. Some still showed the black, charred proof of the boy’s words. But that was almost two thousand years ago, on the Ninth of Av in the year 70 CE. The Romans had pushed burning logs between the huge stones of the Temple. The fire had caused moisture trapped in the stones to expand, breaking the rocks apart and toppling the walls.

Yesterday, that tragedy had seemed remote. Irrelevant to Dan’s life. Part of the far distant past. Today it was…today.

Dan tightened his grip on the child.

“What’s your name?”

“Everyone calls me Dudy,” the child whispered. But my name is Daniel. Daniel ben-Matityahu Ha-Levi.”

Icy fingers clutched Dan’s chest. “But that’s my name!” Did I fall and hit my head, he wondered. Is this a dream? But the boy’s scrawny arm felt real beneath is fingers.

The boy stared back at Dan, his eyes huge. “Your name?”

“I’m…I’m also Daniel ben Matityahu ha-Levi.” A huge knot rose in his throat. He swallowed hard, then coughed in the smoky air. “Everyone calls me Dan.”

Dudy bit his lower lip. He looked Dan up and down. Dan felt as though the child were looking into every corner of his heart. Finally the child spoke. “I never knew anyone with my name before. It’s a sign that you’ve come to help me.”

“How…how can I help?”

“Help me send off Shabano’s pigeons.”

“Pigeons?” Soldiers everywhere, and he’s worried about birds?

“We have to let people know what’s happening!” Dudy pulled on Dan’s arm. “I can’t do it alone.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Dan jumped to his feet. “I’ve got to get out of here. This is crazy.”

“Please! If you don’t help me, who will?”

“But what do pigeons have to do with messages? Use…” His voice trailed off. He was going to say email, or text. But that was crazy, it was the year 70. Oh God, what am I doing here?

Dudy tugged at Dan’s arm.

“The pigeons will carry our notes to our friends in Hebron and Beth-Horon and Aphek and other cities. I can’t reach the ink and parchment, but you could. You’re taller than Shabano. And I can’t tie the messages to the pigeons, Shabano does…did that. My knots always come open. You can tie the knots.

Dan wasn’t so sure, but the child was desperate. He dragged Dan into the house. “Don’t look,” he whispered as he threaded his way between the bodies of his mother, brother, and sisters. The stench of death filled Dan’s nostrils. A sour taste filled his mouth and he swallowed hard, trying not to throw up.

“Hurry. We have to release the pigeons soon so they can leave the city before dark. They roost at nightfall.” Dudy pulled him into another room. “There are the writing things.” He pointed to the wall. High up, almost above Dan’s head, was a niche. In it were several scrolls, a pile of thin parchment, a ceramic bottle with a stopper, and a cup holding several large feathers. Dan glanced around. Except for a stone table pushed against the wall, the room was bare.

“Don’t you have stools? Chairs? Rugs?”

“We burned them long ago, for cooking. When we still had food.”

With a shock, Dan realized that Dudy wasn’t just a skinny kid. He was starved, like the skeletal children of the Holocaust. When yesterday’s guide said that the Romans had besieged Jerusalem, causing terrible starvation, the words had meant nothing to Dan. But starvation clearly meant something to Dudy.

I usually have a snack in my pockets, thought Dan. He felt around. His fingers closed on a stick of gum. Nope, no food value. In his back pocket, though, he found a handful of dates wrapped in a paper napkin. He’d taken them from the breakfast buffet at the hotel, in case he got hungry, then forgot them. He almost passed the packet over to Dudy. Then he remembered a Holocaust survivor who had spoken at his religious school. She’d said that some Holocaust survivors had died the day they were liberated from the camps because they ate too much, too fast.

“Here, Dudy.” He held out one of the dates.

The child’s eyes opened wide. He reached out a dirty hand, then pulled back. “It’s yours,” he whispered.

“I don’t need it. Please.”

The fingers darted out and closed over a date as though Dudy were afraid Dan would change his mind. He brought the fruit up to his open mouth, then stopped. Carefully he opened the date, and stared, dropping the seed on the ground. Then he stretched out his hand, holding the dried fruit up in the air, and shouted two blessings. The second one Dan recognized: it was the third Chanukah blessing, the one said only on the first night. Only then did Dudy shove the date into his mouth and start to chew.

“Eat it slowly!”

Dudy nodded, his jaw working a mile a minute. While he chewed, Dan took down the writing supplies and set them on the stone table. He took a quill from the cup and studied it. “I don’t know how to write with this. And I can hardly write Hebrew.”

Dudy swallowed the last bit of date, then wipe his mouth on his arm. “Thank you, that was…what did you say?”

“I can hardly write Hebrew. And I don’t know how to write with this.” He waved the quill.

Dudy stamped his foot. “I thought you were my friend. You gave me a date. Now you don’t want to be my friend. So go away. If you won’t help, leave me alone!”

“No, Dudy, please!” Dan reached for the child, but Dudy ducked out of his grasp and ran back into the first room. He crouched down beside the body of his mother, tucked his head down, and began to rock back and forth, wailing.

Dan knelt down beside the small child. “Dudy, you have a job. You have to teach me what to do. I’m a stranger here. A…a messenger.”

Dudy froze. He sniffed hard. Then he turned and gazed at Dan. “A messenger? Like an angel?” Is that why you look so strange?”

“I…” Dan hesitated. “I’m a messenger from the future. From a long time away in the future.”

Dudy sat back on his heels and stared. “Are you a Jew?”

“Yes.”

“There are Jews in the future?”

“Yes.”

Dudy ran his fingers over Dan’s arm. He pinched Dan’s sweatshirt, then cautiously touched the sparkly lettering on the front.” You’re real. You’re a Jew. And you’re from the future.”

Dudy’s thin fingers pressed into Dan’s arm as he pulled himself up. “Abba said the Romans will kill all the Jews.”

“They won’t. They’ll kill lots, but they’ll take others to Rome as slaves. Remember when the Jews were slaves in Egypt, and then they were freed? The Jews who go to Rome as slaves will be free one day, too.”

Dudy stared at the ground for a long moment. He sighed and wiped his tear-streaked face with his sleeve. “So God sent you to help. Come.” He clutched Dan’s hand and pulled him back to the inner room. He showed Dan how to dip the quill in the ink, write a few letters until the ink was used, then dip again.

While Dan practiced writing with the quill, Dudy worked on the note. He whispered the words, his tongue licking his upper lip in concentration. In a few moments he smoothed out the note and read it aloud. “9 Av. The Romans have killed many people. They are making the rest slaves. The Temple wall is falling. The city is burning. Daniel ben-Matityahu ha-Levi.”

He put his note on the table. A faint smile crossed his face as he studied Dan’s writing. “Your writing is as slow and as bad as mine. We need nine more copies. We’ll both write.”

Dan looked at Dudy’s note. “I’ll try.” I sure wish I’d studied harder, he added to himself. The two boys bent over their quills. For a long time the room was silent except for the scritch-scritch of feather on parchment.

“That’s all.” Dudy set his quill in the cup and looked at Dan. “Let’s go.” He clutched the parchments in one hand. With the other hand he reached for Dan. “The pigeons are on the roof.”

He led Dan past the bodies into the courtyard. Steps to the roof were built into the courtyard wall. “Keep low so the Romans don’t see you,” Dudy whispered as they climbed to the rooftop.

The smoke was much worse on the roof. To the east, flames danced against a smoke-red sky. Shrieks and the tread of soldiers filled the air. Panic raced through Dan. In spite of the heat, cold fear gripped his chest. I’ll never get home, he thought. Then he glanced at Dudy. The small boy’s face was flushed, his dark eyes burning like candles. “As the soldiers killed Shabano, he yelled, “The pigeons, the pigeons!” He was telling me that I had to send the message since he couldn’t. Now I’m sending it, as he asked. I can die in peace.” He seemed to grow, as though in fulfilling his mission he was becoming a man.

“You…you won’t die,” whispered Dan. The words caught in his throat. He wanted to ask, “Where do you get your courage?” But he know that Dudy wouldn’t understand the question. He was just doing what he had to do. As I am, Dan realized. Holding on to that thought, he fought down his panic.

Then they were at the dovecote. The pigeons fluttered when they saw Dudy. One flew from its open cage, landing on Dudy’s head. Dudy reached up to stroke the bird. “When we ran out of food, we opened the cages. They go out to eat, but they come back. They know this is home,” he said. He opened a metal box, removing fine thread and a small knife. “We roll the message around a leg and tie it,” he explained. “I’ll hold the birds. You roll and tie.”

When each bird was ready, Dudy opened his hands and gave a little toss. The pigeon fluttered, then flew away.

Finally Dudy reached up and lifted down the pigeon that stood on his head. “This is mine.” He kissed the sleek bird’s head. “He’ll fly to my uncle in Hebron.” As he stroked the bird, a feather loosened itself from its wing. Dudy tucked the feather in his belt. When the note was tied securely, Dudy kissed the bird again. Then he raised him high in the air and released him. The bird circled once, then sped toward freedom.

Dudy and Dan watched the bird disappear. Occasionally the younger boy’s shoulders shook, but he was silent. Finally he turned around. “Now we can die, too,” he whispered, taking Dan’s hand.

“The Romans will take many Jews as slaves. They will live.”

“I don’t want to be a slave by myself.”

“You have to go if you have a chance. The Jewish people need to live. You need to live.”

“Will you come with me?”

“I can’t,” Dan said. “I have to find my way back to my own time.” Please, God, get me home, he prayed silently. He reached into his packet and pulled out the napkin-wrapped packet. “Take the rest of my dates. Eat them slowly, one and then wait, another and then wait, so you don’t get sick.” He watched while Dudy tucked the packet into his robe. Then he bent down and hugged the boy. “I promise, you’ll live to have a son. He’ll be Matityahu ben-Daniel ha-Levi. His son or grandson will be Daniel ben-Matityahu ha-Levi, and so on until I’m born.” He stood up drawing Dudy upright. “Do you understand? There will be many generations of Jews, fathers and sons, one after another, from you to me.

Dudy nodded.

The sound of marching soldiers mingled with the sound of shuffling feet. Soon the two boys spied the helmeted heads of soldiers heading a crowd of Jews. More soldiers marched behind.

“Come,” said Dudy to Dan. “I’m ready. We cannot hide here forever.” He pulled Dan down the last steps into the courtyard. Dan waited while Dudy went into the room where the bodies of his family lay. Then the boy came back out. He clutched Dan’s waist and stared into his eyes. “You said before that the Jews will be free. That’s the truth? We won’t be slaves forever?”

“Yes, truly, the Jews will be free. It will be a long time, but we will.”

Dudy nodded. “Then I’ll go. I’ll stay alive for my family. And for you, Daniel ben-Matityahu ha-Levi-from-the-future. Come.”

Dudy pulled him through the hallway to the plaza. A moment later the Romans rounded the corner. A stocky soldier poked at Dudy with the flat of his sword. “Get moving.”

Dudy tugged at Dan’s hand. “Come, Dan,” he whispered.

“Move on, dog!” The soldier raised his sword at Dudy, ignoring Dan.

“Go, Dudy. He doesn’t see me,” said Dan.

Dudy released Dan’s hand. He pulled the pigeon feather out of his robe and handed it to Dan. Then he ducked past the soldier into the crowd. “Goodbye, angel,” Dudy called. “Goodbye.”

Dan watched until Dudy was out of sight. Now he could feel the fire approach. As he dropped the feather into his pocket, he felt the small metal coin. He rubbed the pomegranates once, twice, three times.

The sky darkened, and sound quieted. A damp chill replaced the hot, smoky air. Now the only light was a small square of dimness. Dan turned and crawled through the opening, toward the light that glimmered far ahead.

As he approached the tourist tunnel, Dan could hear people coming, footsteps, and the welcome sounds of English. Through the opening he watched a parade of Nikes, Reeboks, and Teva sandals. Shoes from his own age. A weight lifted from him.

When the last pair of feet had passed, Dan scrambled into the tourist tunnel. Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out the coin. He held it by the rim, careful not to rub it. Spotting the small crevice from which he’d taken the coin, he jammed it back. “There,” he thought. “Now it’s safe.” Then he studied the irregular surface of the stone that had opened into the tunnel, looking for a way to pull it forward. Grooves ran a few inches back from the front edge along both sides of the block. Using these hand-holds, he tugged at the stone.

As though greased, it slid easily into place, sending him back onto his heels. He pressed his hand to his chest, catching his breath. Then he eyed the wall. The stones looked as though they’d never been disturbed. He shook his head, then stood up. He straightened and stretched. Somehow, he felt bigger. Older. Or maybe wiser than he’d been before his adventure had started. He reached into his pocket again, closing his fingers around Dudy’s gift. He pulled out the soft, gray feather and stroked it across his cheek. Then he tucked it back into his pocket and sprinted after the retreating tourists.

This story appears in Ghosts and Golems, compiled by Malka Penn, published in 2001 by Jewish Publication Society. Story copyright by Hanna B. Geshelin.

For Parents, Teachers and Others

The Romans spent four years conquering Judea, from the year 66 CE (AD) to 70. In 70 they besieged Jerusalem, the capital, causing starvation, disease and death. On the 17th of Tammuz (late July-early August) they breached the wall and three weeks later, on 9 Av, they sacked and set fire to the Temple and took the majority of the survivors slaves to Rome.

To the south-west of the Kotel there are still massive stones near the path, charred from this destruction.

This campaign was documented by Flavius Josephus, who was born in Jerusalem around the year 37 and died in Rome in the year 100.1 A massive arch was erected in Rome commemorating this victory. Among other carvings is one showing slaves carrying the Menorah that had stood in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Bar Mitzvah Celebrations

For many American youth whose exposure to Judaism has been in the liberal, more assimilated branches of Judaism, there is little link to God or Jewish law. Youngsters have told me that they do not feel a connection to Israel, God, or Jewish tradition; why would they when the crucial bits have been removed?

For most of these children—unfortunately the majority of Jewish children in the USA—the bar or bat mitzvah is an occasion for learning a tiny bit of Torah and a couple of prayers in order to read or explain something at a synagogue service, and a big party. Liberal Judaism is based on the premise that (most) Jewish law, including religious obligation, is archaic if not outright arcane and not relevant to today’s life. This means the traditional meaning of these milestones—the passage of the young person from childhood to adulthood that bestows religious obligations—has been lost. Most of these youngsters have no Jewish education beyond bar- or bat-mitzvah preparation, although some will continue through confirmation (a milestone created by liberal Judaism with no basis in tradition).

Some families bring their families to Israel and have a bar mitzvah at the Western Wall (the Kotel), the remaining part of the Temple in Jerusalem.

For more information about bar- and bat-mitzvahs, see my July 2, 2024 story, “What is a Bar Mitzvah?”

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed July 28, 2024.