Ishvi's Temple Miracle

Yom Kippur in Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, historical fiction for children 9-14.

Ishvi woke up shaking as the old nightmare filled his mind. He was once again 6 years old, and as a treat his father had taken him to the market in a nearby town. But oh, the crowds! People—strangers—everywhere! Someone brushed by him and he let go of his father’s robe for just a moment. But when he grabbed for it, a stranger looked down. He remembered screaming Abba! Abba! The stranger picked him up and shouted, “Whose son is this?”

The sea of strange faces still haunted him. How would Abba ever find him? Would he be lost forever? The old terror gripped him; he could hardly breathe. Then he remembered that he wasn’t 6 years old. He was a bar mitzvah, a young man past his 13th birthday, with many of the responsibilities of an adult. He took slow breaths the way his father had taught him. Slowly his heart calmed to its normal beat.

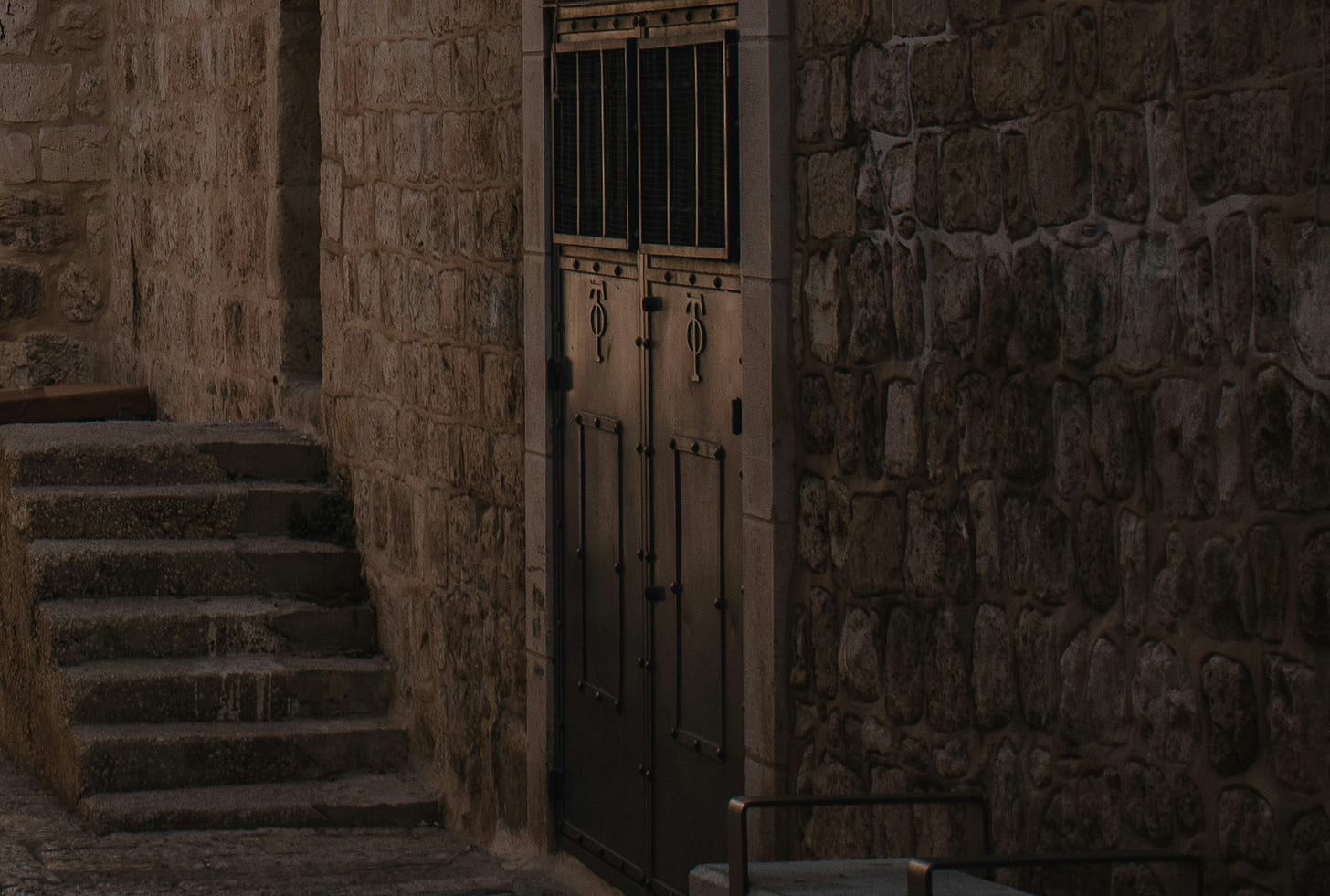

Light began to creep around the edge of the door, chasing away the dark. He pushed up until he rested his back against the wall, knowing he was done with sleep. This very day he was going to begin the long journey to Jerusalem with his father.

The two of them, along with his uncle and cousins, would leave soon after the sun was full up. The produce from their herd of sheep--cheeses his aunt made and the fine, smooth yarn his mother and sisters spun—earned better prices in the big city of Jerusalem than in their village, where most people raised sheep, spun wool and made cheese. In the city, they would also serve God in the Temple.

The plan was to arrive before Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, and attend the special Temple service that day. They would stay in Jerusalem for the Sukkot pilgrimage holiday, too.

He knew that near the capital city the crowds would increase. His father had said, “You are tall, and your help to me on the farm has made you strong. Uncle Shamma and your cousins will be with us. Shomer has come twice, but this is Heber’s first time too. You have nothing to fear.” But that scared little 6-year-old still lurked in Ishvi’s heart.

After morning prayers and breakfast, Abba, Uncle Shamma, Ishvi and his cousins checked that all their bundles were safely packed on donkeys. At last they started off.

The road twisted across the mountains, up to villages on bare mountain tops and down into the shade again. It avoided the bottoms of the deep, narrow valleys that were filled with snakes, wild boars, and other beasts.

From the forested hills of home they soon came to those covered with grasses and low plants. Ishvi turned his head from side to side, amazed at the beauty all around. At noon they stopped at a tiny village where they traded a few skeins of yarn for a wonderful dinner. Then they lay down in the shade and napped.

Exhausted from his sleepless night and the long walk, Ishvi fell into a deep sleep. But his nightmare struck again. In the dream he kicked at the stranger who was lifting him high. Even though he was sleeping, his foot jerked and hit Heber.

His cousin punched him. “Why did you kick me?” he whispered.

“I - I didn’t mean to. I was dreaming,” Ishvi answered.

“Are you still having that baby dream from that time you got scared at the market? Didn’t you have your bar mitzvah? Or are you still a baby?”

The taunt from his cousin wasn’t new. Heber was almost a year older than Ishvi, but Ishvi was a better student and a better worker than the bigger boy. For years Heber had controlled Ishvi by unkind teasing about that dream and about any other thing he could think of. This time, Ishvi didn’t answer. He rolled over on the other side so he faced away from his cousin and pretended to fall back asleep.

The sun was moving toward the western sea when Abba woke them all up. They stretched, checked their bundles and their donkeys, then took off again.

The hills were lower here and the road easier. Before dark they were at a larger town. They found the small bet knesset, the prayer house. After prayers they were invited for the evening meal. “I have a large barn,” the man said. “There’s plenty of room for you to pen your donkeys and still have room to sleep.”

This time Ishvi made sure to sleep far from Heber.

By the end of the second day, Ishvi knew they were nearing the city. The road they followed was wider here and filled with travelers. Carts and donkeys traveled up and down along with more people than Ishvi was used to seeing in a whole day. His knuckles were white from gripping the donkey’s lead so tightly.

Heber shoved at the donkey that Ishvi was leading, making the animal take a few dancing steps. “Leave my donkey alone!” Ishvi snapped.

His uncle turned around. “Ishvi, behave,” he said.

Ishvi bit his lip. Arguing with an older relative was not respectful. And anyway, Uncle Shamma always took his son’s side, and Abba usually followed his big brother’s lead.

Ishvi worried what would happen when they reached the busy capital city. Would Heber make real trouble for him, not just these little nudges?

That night, he remembered that his peace-loving mother had told him that if he stopped responding, Heber would stop teasing him. So after saying his goodnight prayer, Ishvi prayed that God would give him courage and the ability to let Heber’s taunts go. Maybe because of this extra prayer, or maybe just because he was so tired from two long days of travel, Ishvi slept soundly through the night.

Early the next afternoon, the little family group reached Jerusalem. Ishvi stared at the wall surrounding the city. Inside that wall were thousands of people. Again his heart started to pound. He felt the sweat break out on his forehead and he knew it was from fear. Getting lost here would be much worse than getting lost in the market of a small town.

Heber elbowed him. “Getting crowded, isn’t it?” he whispered. Ishvi made a fist and pulled his arm back, ready to punch his cousin. But they were about to enter the city where the holy Temple was. The city that held the home of God on earth. He took a deep breath, opened his hand, and let his shoulder drop.

After they reached the inn where his father and uncle always stayed, Uncle Shamma, Heber and Shomer went off to visit an old friend. As Ishvi and Abba ate supper at the inn, Ishvi asked what would happen at the Yom Kippur service in the Temple. Abba described the beautiful robes of the priests. He told how the Kohen Gadol—the high priest—would enter the Holy of Holies several times, changing his clothes each time before he entered and after he came out.

Ishvi listened, his forehead furrowed. “But what does it feel like?” he asked.

Abba gestured with his hands as he tried to describe the feeling of awe at being in God’s holiest place on earth. Ishvi shook his head and bit his lip. Finally he asked, “Is it crowded?”

Abba put his arm around Ishvi. “Are you still worried about crowds? We will stand together. It’s crowded, but people stand pretty still. And remember, back when you were young you were so small that you could just see feet and the robes covering legs. Now you are tall. You can see better. Don’t worry.”

But Ishvi worried. He worried so much he hardly slept that night, and most of the next day.

The afternoon before Yom Kippur, they all bathed and put on their best clothes. But he could hardly swallow a bite of the seudat mafseket–the last meal before the fast--in the inn. Then, just before sunset, they went to the Temple.

The road that that morning had been empty was now crowded with people moving toward the Temple. Abba was right: Ishvi could see over most of the shoulders. Abba was tall, too; it would be hard for them to lose sight of each other even in the crowd.

Once inside the huge courtyard, Ishvi stared at everything. Even when the Temple service began, he couldn’t concentrate. Everything was so new! He tried to remember everything. Men wore intricately woven robes, colorful belts and more that his sisters would want to hear about, and his mother would want to know about the songs that the Leviim sang.

The next day, the crowd was even larger. The men were packed together, shoulders and hips bumping. Ishvi stood between his father and uncle, as far from Heber as he could. He rolled his shoulders and breathed deeply, trying to relax so he could pay attention to the priests.

Then, hours after the service began but long before the ending, his father whispered to him, “Now comes the Aleinu prayer. Instead of bowing the way we normally do, we prostrate ourselves: we kneel down and put our foreheads on the ground.”

Ishvi’s mouth dropped open. How was it possible? The men were packed together shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip, with no space between. How would there be room for everyone if they had to do that? He bit his lip and blinked fast as the old terror roared through him.

Just then, at the right place in the prayer, everyone knelt, then bowed forward until their foreheads touched the ground. Abba put his hand on Ishvi’s shoulder and pushed gently. Eyes huge, biting his lower lip, Ishvi lowered himself.

To his astonishment, he had plenty of room to bow down! In fact, there was room for every person. For the first time since entering Jerusalem, he breathed freely as the men knelt down. They stretched out their backs until their foreheads touched the pavement. Together they recited the familiar prayer:

And we bend our knees,

and bow down,

and give thanks before the Ruler,

the Ruler of Rulers, the Holy One, Blessed is God.

The One who spread out the heavens,

and made the foundations of the Earth,

and whose precious dwelling is in the heavens

above, and whose powerful

Presence is in the highest heights.

Adonai is our God, there is none else.**

As he lay there, flat on the pavement with his eyes closed, a feeling of joy and wholeness dropped gently over him, like his mother shaking a warm blanket over him on a cold night. But it was so much more than a woolen blanket! His heart seemed to open as love filled him: love for God, love for his father, mother and sisters, and even love for Heber.

Behind his closed eyes he could almost see God’s mercy, love and concern settling over the huge crowd. He understood that all am Yisrael, the whole Jewish people, were one family cuddling together beneath God’s care.

The moment was short; all too soon the crowd rose and continued the prayer. Again they were shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip. But the other people were no longer scary strangers. They had become part of Ishvi’s larger family, the Jewish people.

With his heart swelling with love and joy, he peeked behind his uncle. Heber stared at him, biting his lip. Ishvi knew there was no reason for him to fear his cousin. It would be easy, now, to ignore his cousin’s teasing.

Then Heber shook his head and gestured to his heart. Ishvi grinned back. His cousin was apologizing, and Ishvi understood that Heber had also felt God’s love.

Later that night, after the family had broken their fast with the other men at the inn, he remembered how at one moment the Temple courtyard had been crowded, and then suddenly it grew so that there was plenty of room for everyone to lie down. And when they stood again, it had returned to its original size. It had been a clear miracle, proof of God’s presence.

But Ishvi didn’t need that proof. The feeling of love and unity among the horde of men, and between him and his cousin, was enough.

*Jodi Sugar’s 16-month 2024-2025 (Hebrew year 5785) calendar is still available at https://www.jodisugar.com/israel-calendar .

**Translation of the traditional Aleinu prayer from www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/aleinu .

For Parents, Teachers, and Others

The message of Yom Kippur is not easy to teach children, but in my story at the beginning of Elul, Blaming Alex, I gave a hint. For this story, I wanted something different.

At the time I am writing about in this story—sometime during the existence of the First Temple—as in Orthodox synagogues to this day, men and women were separated in worship. So this is a story focused on males.

According to Pirke Avot, Ethics of the Fathers, 5:8, says: “Ten miracles were wrought for our fathers in the Temple.” One of the miracles is Though the people stood closely pressed together, they found ample space to prostrate themselves.1 The explanation for this is that the Temple miraculously grew to accommodate all the people, and then returned to its original size.

The first few years after I became religiously observant I found the custom of prostrating during the Aleinu on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur outlandish, but after I became accustomed to it, I started to feel a strange connection with my ancestors. Over the years, it has become for me a treasured moment of the synagogue service. If in recreating this custom I feel something extraordinary, what must the men in the Temple have felt? Probably the Talmud explains this in detail, but I am writing here purely from my imagination.

If you normally look for my posts early Tuesday morning, my apologies for being a day late. Due to the Hezbollah war I spent the Monday after Rosh Hashana in the “safe room” (reinforced home bomb shelter) of a friend, without access to my computer, so I did not finish in time. My old apartment does not have a safe room.

My plan now is to buy a good laptop and get rid of my antique desk-top computer so that I will not be caught like this again. You can help prevent this inconvenience by becoming a paid subscriber, thus helping me with this purchase.

Hertz, J. H., ed., Sayings of the Fathers or Pirke Aboth, Behrman House Inc., 1945, p. 87.

A warm beautiful story