Repentance: the Work of Elul

The month of repentance is followed by our new year and Day of Atonement. What does it all mean?

Elul: The Jewish Month of Self-Reflection

Elul, the Hebrew month that precedes Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, is a month of self-reflection. We believe that during Elul, God makes Himself more accessible to us, as though a king had left his palace and was walking through the fields where anyone could approach him. In many synagogues, the shofar (ram’s horn) is blown during daily prayers, calling to our souls to repent.

On Rosh Hashana, the start of the year, God decides what our fate will be for this new year. On Yom Kippur, after a day of penitential prayers, He seals the book. (Some traditions say He decides on Rosh Hashana, signs on Yom Kippur, and seals the book with finality for the coming year at the end of the Sukkot holiday, which follows a few days after Yom Kippur.)

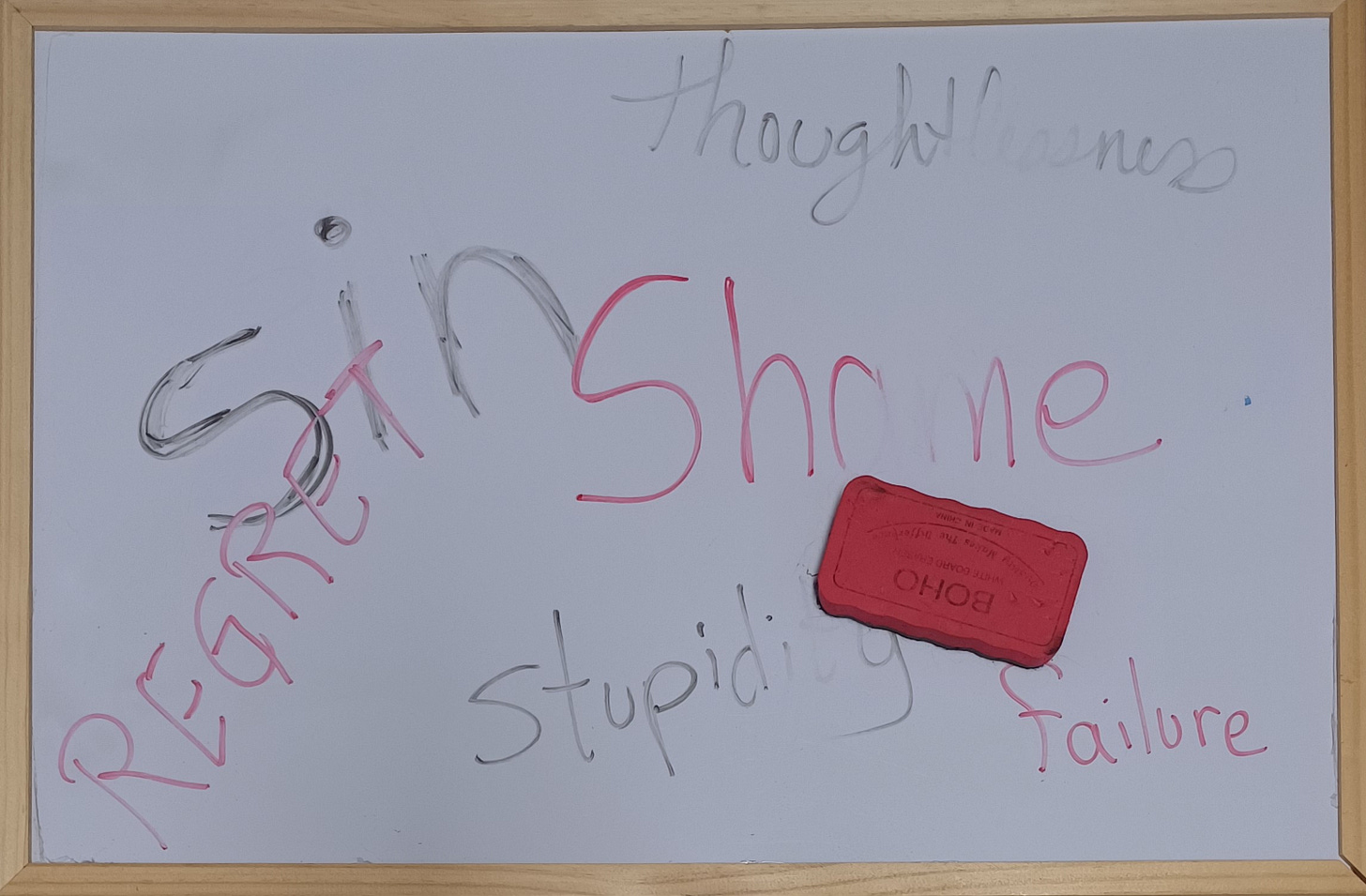

We all have character faults, but mostly they are so much a part of us that we do not recognize them. Last week I published a child’s story about blaming and accepting blame. This is just one tiny aspect of behavior that needs to be looked at during Elul. In the effort to refine our characters, many Jews look at long lists of issues for which people need forgiveness. These are so important that they are repeated several times during the Yom Kippur prayers:

The Ashamnu: We have transgressed, acted perfidiously, robbed, slandered, acted perversely and wickedly, willfully sinned, done violence, imputed falsely, given evil counsel, lied, scoffed, rebelled, provoked, been disobedient, committed iniquity, wantonly transgressed, oppressed, been obstinate, committed evil, acted perniciously, acted abominably, gone astray, led others astray.[i]

The Al Chets: sins committed under duress, by hardheartedness, inadvertently; through uttering or immorality, openly or in secret, with knowledge and deceit, through speech, through deception, improper thoughts, being among lewd people, insincere confession, disrespect for parents and teachers; whether committed intentionally or unintentionally. By using coercion, by desecrating God’s name, by impure speech and foolish talk, by falling for the lures of the Evil Inclination, knowingly or unknowingly.

We recite these lists in the plural. With each individual sin we say, We do this.

Individually we are very rarely guilty of all of them, but they are all done in in our communities. We permit them—for example, by not stopping others who do them and by not exiting places or groups where they happen—and so have culpability. And like Yael in last week’s story, we don’t want to be blamed for being imperfect.

But we are imperfect. Judaism doesn’t teach that we are born sinful; we believe we are born neutral, with the capacity for great goodness and great evil.

We often feel guilty of wrongdoing, of our imperfections, of letting our evil inclination take over, however briefly. But these feelings do not create change. To change, to grow and strengthen our characters, takes work. Elul, with its acknowledgment that come Rosh Hashana God will be judging us and deciding who will live and die, and how we will live or die, is set aside each year to help us.

Asking Forgiveness

Part of our character and soul correction is the necessity of asking forgiveness of those we have wronged. It is not enough to ask God; He will forgive us if and when we have tried to correct our errors and failings with the people involved. Note that I did not write that we need to convince these people to forgive us; that is beyond our control. Our job is to repent and ask forgiveness, sincerely.

And we are encouraged to accept sincere apologies; that too is on us. We are not obligated to forgive people who have not asked forgiveness. “I forgive Hitler,” for instance, is considered inappropriate. But we should let go of the pain of being wronged: it happened, it is over, it cannot be undone; I am sorry, I have mourned those loses, and I will continue my life having learned and grown from it.

Children and Elul

Everyone makes mistakes: children and adults, even parents and teachers. Learning the lessons of Elul early helps children understand themselves, those around them, and the world in a healthy way. When they are aware that no one is perfect, and that there is a real way to get over feeling guilty about honest mistakes—and even things done deliberately for which they are later sorry—they are free to experience life without the shame that otherwise comes from failure.

Youngsters in the early grades are learning to see themselves as parts of the larger world. The independence of a two-year-old is different from that of a child beginning grade school: at two, children are learning they are separate from their parents. Six-year-olds are learning that they are part of a family, a class, a neighborhood. An eight-year-old is learning what it means to be part of a larger group—a city, state, nation, a people.[ii]

At each age, children approach different sins differently. They are also individuals, so each one trips over different transgressions. But kids feel shame and embarrassment, two payments for having done wrong.

It is critically important that children understand that forgiveness for transgression is a two-way street: We acknowledge to the individuals we hurt and to God that we have sinned, and He forgives us when we sincerely want to do better in the future.

As I write this, I remember my sister once told me that a college roommate had said that she loved the Catholic church because she could do whatever she wanted, confess to the priest, do her penance, and repeat. I strongly doubt any priest would agree with her assessment. We Jews certainly do not believe that; our confession and atonement must be sincere. Children need to understand this difference. They need to know that saying we want forgiveness but keeping in our minds that we will continue to do the problematic act does not sit well with God.

Children also need to learn to accept God’s forgiveness, whether they feel it or not. They need to learn to set down the burden of wrongdoing and leave it in the past. Beginning to teach them about Elul, repentance, confession, and atonement at a young age can facilitate this process. If they are only taught this when they are a little older and perhaps have done some serious harm to themselves or others, it will be harder for them to believe that God forgives.

In secular American society it is considered weird to have someone apologize for something that they did months earlier. In Judaism it is appropriate and common.

An example from my past

When I was in my early 30’s I moved from Idaho to the Boston area; I was looking for a deeper connection to Judaism. For about four months I shared an apartment with two women, one of whom brought passive aggressive behavior and gaslighting to the level of fine art. She moved out and I did not see her again—until about 15 years later. By that time I was firmly settled into an Orthodox lifestyle, but I had friends from across the religious spectrum. One invited me to attend a monthly group that she found spiritually very satisfying. I went during Elul. The group activity that evening was to share something that we had felt badly about but for which we could not or had not asked forgiveness.

About half-way through the evening, my former roommate walked in. I thought about walking out, but did not want to make a scene. Her turn to talk came before mine, and she told about having been guilty of terrible behavior in the past but had been encouraged to have counseling about it. The things that she said she wished she could apologize for were the exact things she had done to me—clearly she had seen me, and equally clearly, she remembered how she had wronged me. When my turn came, I said that I had had a roommate with whom I had not gotten along. While I had blamed her, I had not considered how I might have contributed to the bad relationship, and I wished I could apologize. After the activity, we went directly to each other and shared a very healing hug. No further discussion on the past was necessary. I never saw her again, but until that evening I had not realized how heavily that terrible relationship had weighed on me.

Conclusion

I hope you, my adult readers, can find something not just interesting but useful in my explanation of Elul, sin and forgiveness. I know that both Catholicism and Judaism have formal paths for receiving forgiveness; I do not know about other Christian practices. And I have observed that in the secular world, it appears to be common to adjust one’s beliefs about right and wrong rather than to admit error. I hope all of my readers find this little lesson on Jewish practice helpful in some way.

[i] Translation for both this and the following paragraph are from Machzor for Yom Kippur, edited by Rabbi N. Mangel, Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, New York, 2006.

[ii] https://raisingchildren.net.au/school-age/development/development-tracker/6-8-years#child-development-at-6-8-years-whats-happening-nav-title

I saw your email of this article come in and I thought, oh good, I know I'll learn something deep and useful. And I did! It gave me a lot to heal in my life.