Passover Suitcase

A Passover story about life for Jews in the Soviet Union. Ages 8-12.

Passover was coming. Mama cleaned our large room carefully to get rid of the hametz that is forbidden on the holiday. She even washed all the bedding and the curtains.

“Spring cleaning,” she told our neighbors in the kitchen all four families shared. I knew my parents were afraid that the neighbors would turn them in to the KGB, the secret police, if they thought we were following any Jewish customs.

She scrubbed every bit of the floor. “My Soraleh brought home a kitten one day,” she told the neighbors. “It was only inside for an hour or two, but I think I saw fleas.” The other ladies nodded. They did not want fleas in the apartment either.

When we went walking after supper, outside in the still-cold night, she said to Papa, “I am worried. How will we get matzos this year? Your mama always brought them, but she wouldn’t tell us where she got them. And this year she is too sick to go.”

Papa rubbed his chin. “I don’t know,” he finally answered. “And I don’t know how we could get them, even if we knew. She carried them against her stomach. No one could see them, she just looked like a fat old lady. But you or me, the police might see. Or our neighbors might be curious.”

I followed behind, listening. I knew what they meant. Matzos were against the law. Having a Passover seder was against the law. But we were Jews. We would have a seder, quietly in our room. We would not tell the other families who shared our apartment. If they saw Mama or Papa carrying something big and flat they might wonder. And if they found out, we would have trouble.

Mama and Papa started talking about Papa’s work. I stopped listening and just looked around. A piece of newspaper blew across the road and bumped into a building. A scrawny cat slinked along the foundation and squeezed behind the newspaper.

My friend Anya from school rushed along the sidewalk carrying a suitcase. “Hi Anya,” I called. “Where are you going?”

“My mama is sick. I am going to my uncle’s so that I will not get her sickness,” she said. We talked for a moment longer. Then she said goodbye and hurried off.

If I had to go to my grandmother’s at night, my father would carry my suitcase, I thought. He would not let me go alone that late. I did not know whether to be envious of Anya for her freedom, or sad that she didn’t have a father to keep her safe.

That night I dreamed of going to grandmother’s by myself with a suitcase. The dream seemed very real, but I didn’t think much about it. It was just a silly dream.

The next night I had the same dream. And the next night. The same dream, three nights. I thought of the story of Pharaoh. He had a dream about fat and skinny cows three times in a row because it was an important message. Maybe mine was important, too.

A few days before Passover Mama, Papa and I went to visit Papa’s mother. She sat by the window, pale and thin. After a few moments Mama said, “Visit with Grandmother, Soraleh, while Papa and I speak to the house committee. Soon we might need to move Grandmother to live with us.”

I sat near Grandmother. I took her bony hand and rubbed it gently. “Grandmother, where do you get matzos?” I whispered to her. “I have a plan to get them.”

Grandmother turned her head and looked at me. “Tell me your plan.”

“My friend Anya went to her uncle’s alone, carrying her suitcase. The police did not stop her. They would not stop me, I’m just a little girl. I would put my nightclothes and my snuggly doll in the suitcase, so if they stopped me I could open the suitcase and show them. I could put the matzos in the suitcase, under my nightgown, and bring them home.”

Grandmother thought for a moment before replying. “Small children helped when the Nazis came. You are a brave, smart nine-year-old now, you can do it.” She whispered the address to me. I repeated it several times. I liked numbers. I would not forget. Then she made a plan. “We will not tell your parents,” she said. “The fewer people who know, the safer.”

Then Grandmother told my mother that she would like me to stay overnight the next day so that I could help her clean for Passover. My mother agreed. She was glad that she did not have another room to clean.

The next day after school, my mother told me I just needed a sack to carry my nightgown to Grandmother’s. I asked if I could take the suitcase because when I cleaned, Grandmother might decide to give us some things she did not use. My mother nodded. Grandmother had thought of a good story.

When I left with the suitcase, I worried that our neighbors might ask where I was going. They might think it was strange that I was going to spend the night at my grandmother’s.

No one asked.

I went to the address my grandmother had given me. When I knocked, a woman cracked open the door. “I am Bassie Kogan’s granddaughter,” I said. The lady nodded. “You look just like her,” she said, pulling me inside.

The lady put the matzos in a clean, old towel. We put them in the suitcase and put my nightgown and my doll on top. “You are a brave girl,” she said. “Be safe.”

She peeked out the door, then waved me over. “Give me a hug in the doorway,” she said. “If anyone sees I will say you are my cousin’s daughter.” I hugged her and started off.

When I saw a policeman, my heart started to pound. I thought about running, but decided that would look odd. Instead I just walked. When the policeman noticed me he nodded. All he saw was a little girl with an old suitcase. He didn’t see a Jew carrying matzos for Passover.

Soon I was home. My neighbor who lived in the next room saw me enter the apartment “What are you doing with that suitcase?” she asked.

“I was going to spend the night with my grandmother so I could help her with some chores, but she has a headache so I came home instead,” I said.

When I showed my parents the matzos they were angry and happy at the same time. They were angry I made such a dangerous trip, but they were happy to have the matzos.

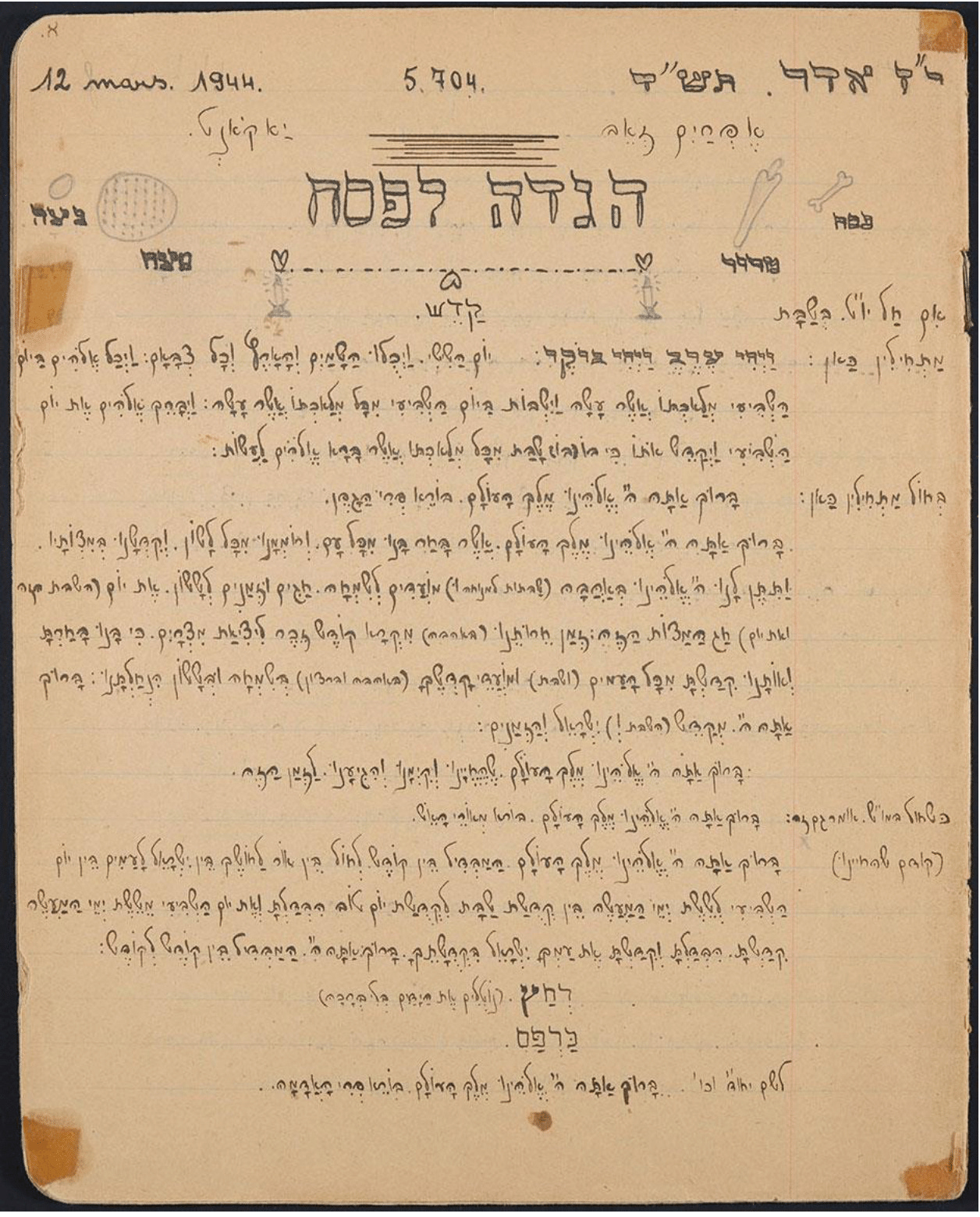

The next night was Passover. We were lucky. We had a copy of the Haggadah, the story of Passover that we read at the seder. It was against the law to print a Haggadah. It was even against the law to own one. But years before, some very brave person had printed some copies on a machine at home. They were purple on white paper. He gave the copies he made to people he trusted. Then each person made his own copy and passed the purple on to someone else.

I remembered when Papa had copied it out. Mama read it afterwards and compared it to the purple so that Papa could fix any mistakes. Every word had to be exactly like the original, Mama explained. Now the copy was old. It had been folded and unfolded so many times that it was starting to tear along the creases. Papa kept it in a picture frame, behind the photograph of his grandparents who had been killed by the Nazis.

We ate our matzos and prayed that one day we, too, would be free like the Jewish slaves who left Egypt.

That prayer came true. When the Soviet Union ended, we left Russia and came to Israel. Here we are free. We can buy matzos in any store, and we read the story of Passover in Hebrew, even my youngest child. My children cannot imagine not being free.

I tell them the story of my suitcase, my nightgown, my snuggly doll, and the matzos. And I tell them, “Never forget. And always be thankful that you are free.”

For Parents, Teachers and Others

Life for almost everyone was difficult in the Soviet Union, but it was especially difficult for Jews. On the mandatory identity cards, Jews’ nationality was listed as Jewish, even if only one parent was a Jew. Judaism, as other religions, was outlawed, but there was a special animus toward Judaism.

In the USA I had a friend whose father had given clandestine classes on Judaism, but the classes became known to the KGB, the Soviet secret service. He was warned to stop, but he continued. His wife, my friend’s mother, was then killed on a clear, dry day by a hit-run driver.

An acquaintance, who had lived in a small community with few Jewish residents, told me she had been a civil engineer. What that meant in the Soviet Union, however, was someone who used a maul to break rock into gravel for road beds. This woman, at the age of 30, looked like a woman of 60. She had been breaking rock since she was 14. She explained to me that there was only one high school in her town, and the principal was an antisemite. In the USSR there were exams given to 14-year-olds that determined whether they would continue on a college-track program or begin work. She was sick the day of the exam, and contrary to law the principal refused to let her take the make-up test, failing her instead. Then the government assigned her the road-building job which she held until the Soviet Union collapsed and she was able to emigrate to the USA.

Anti-Jewish quotas were common, Jews were refused promotions or fired for no cause, and possession of Jewish artifacts could be very dangerous. Samizdat , or clandestinely printed material passed from hand to hand, was an important form of communication.

This story is fictitious, and the details of the child’s life are largely conjecture on my part. I found that the Russian Jews I know in Israel do not like talking about those days. However, an adult English student told me a bit about her life, and told me that her grandmother used to obtain matzos that she carried secretly in an old suitcase. This became the germ of this story.

This picture is of a hand-written Haggadah used during the Holocaust. There have been many times, including in recent years, that we Jews have had to use stealth and secrecy in order to practice our religion. This is one reason that Israel is so important to the Jewish people.

Very impressed with this wonderful story!