Night Noise

A Passover story for all kids 9-14, based on a true experience

Logan Rothman shifted in his seat and yawned. He had already fought to stay awake during regular school. Now he just wanted religious school to be over so he could go home and lie down. He was sooooo sleepy!

Three weeks ago his family had moved across town from a small apartment to a house of their own. The new house had two stories plus a basement. The basement had one bedroom, a bathroom, and a big unfinished area that Dad promised would one day be a clubhouse for Logan and his brothers. That bedroom was Logan’s.

He’d been really excited to have his own room, but now he longed for the small room he had shared with his younger brothers, twins Joseph and Jackson.

The new room was a nightmare. Every night, several times during the night, loud metallic bangs woke Logan up. “Woke up” was too gentle. They were so loud and so sudden that he practically flew out of bed, heart pounding like a drum set. Then it took him forever to fall back asleep.

But the noises didn’t get to the second floor, where everyone else slept. His parents had not taken his complaints seriously. And although the furnace man had come twice, so far the problem had not been solved.

Meanwhile, in class Ms. Fagenbein droned on about archaic customs of Passover. “Archaic” was one of the teacher’s $10 words, and since Logan loved words he’d written this one with its definition: ‘very outdated; past its time of usefulness.’

To be fair—and Logan generally tried to be fair—Ms. Fagenbein was usually interesting, and he loved the way she peppered the class with big words which she always explained. But Logan did not want to be there. He just wanted to lie down before dinner, while his mother thought he was doing homework.

Finally, at long last the bell rang. He grabbed his backpack and sprinted for the door.

His dream of time to catch a nap was busted, though. A new furnace man was crouched in front of the furnace, which had its metal sides removed. As he tinkered with the innards he described what he was doing to Logan’s father. Logan dropped his backpack on the floor by his desk, kicked off his shoes, and joined his father near the furnace.

Finally the technician put the furnace back together and stood up, dusting off his knees. “Everything is in order,” he said. “I can’t see any reason for loud noises. Perhaps your son is having bad dreams. Maybe he’s too young to sleep down here alone. Or perhaps he just has an overactive imagination.” Logan fisted his hands and bit his lower lip trying not to say something rude. He’d been rude to the other furnace guy and had lost his electronics privileges for the weekend. He wasn’t dreaming, and he wasn’t imagining anything. The furnace made a racket and kept him from sleeping.

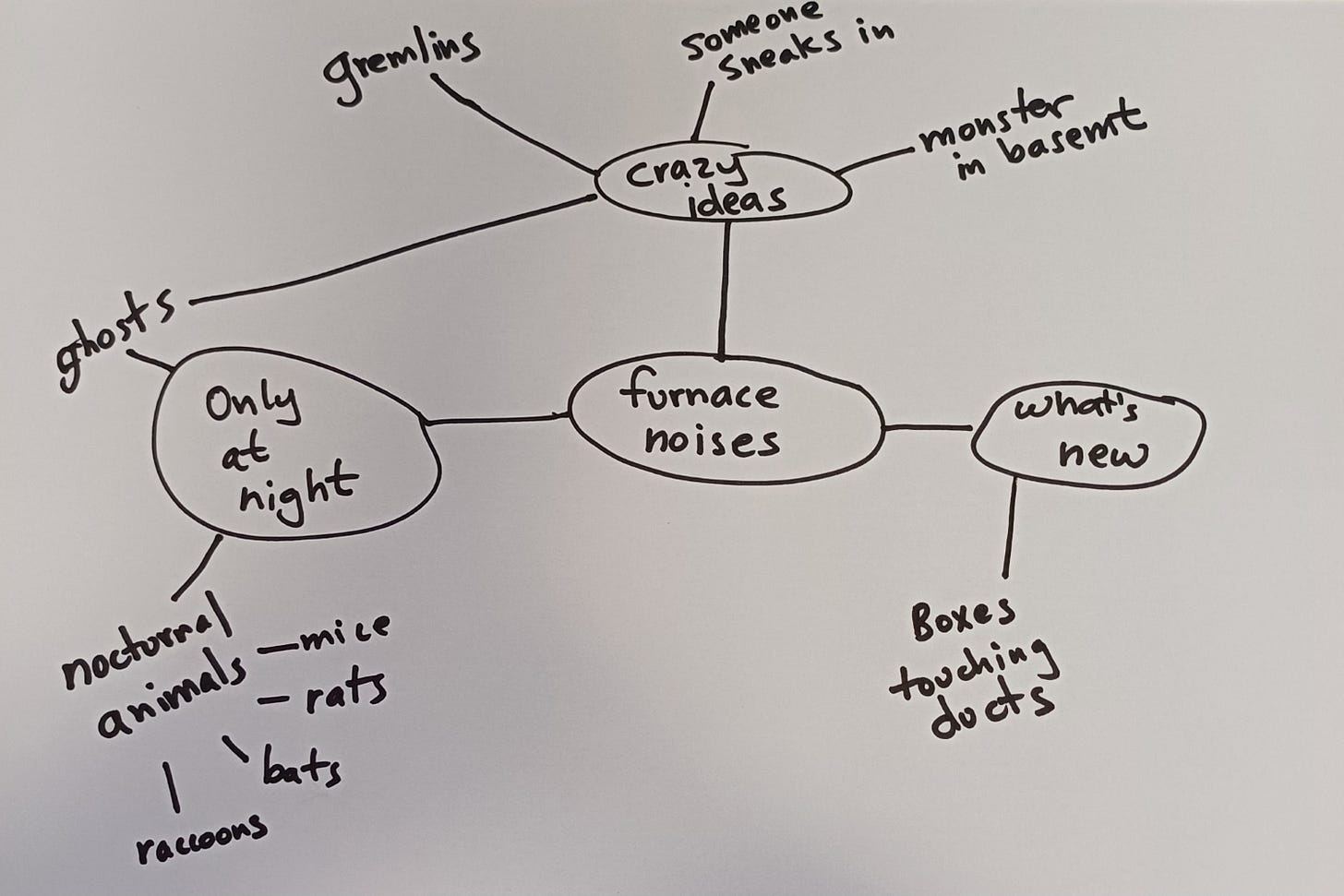

“I’ll have to solve this myself,” he thought as he finished his math homework later that evening. Pushing his schoolbooks aside, he pulled out a blank piece of paper and drew a circle in the middle. Sometimes drawing a web gave him ideas.

In the circle he wrote “furnace noise.”

Off to the left he made another circle in which he wrote, “Only at night.”

On the opposite side he made a circle and wrote “What’s new.”

Between them he drew a circle and labeled it “Crazy ideas.”

From the words “crazy ideas” he drew a spoke and wrote “monster in the basement” on it. On another spoke he wrote “Someone comes in during the night and bangs it.” “Gremlins,” his mother’s favorite word for unexplained happenings, went on a third.

Tapping the eraser against his teeth, he pondered “only at night.”

“Nocturnal animals,” he wrote. “Nocturnal” was one of his favorite words. He’d learned it from an animal book when he was in third grade; it meant “occurring in night.” On spokes off that word he wrote, mice, rats, raccoons, bats.

He looked at the words “what’s new.” The move was new. Maybe the house didn’t like the newcomers? He drew another spoke between “crazy ideas” and “only at night,” and wrote “ghosts.”

But he was too tired to think more. Putting down his marker and yawning, he shut off the light and climbed into bed for another restless night.

In school the next day, he leaned forward. “Barak,” he whispered, “how do you catch mice and rats?”

Barak turned around, scowling. “Are you a racist? You think because I’m Black I live in some slum with rats and mice?”

Logan blinked hard. “What? Of course not! You like animals, you want to be a vet, don’t you? That’s all. I think there might be an animal in the basement where my bedroom is, and I don’t know how to find out.”

“Boys,” warned the teacher.

“Huh,” said Barak. “Talk to me at lunch.”

The next day Barak brought a big sack to school and handed it to Logan. “It’s a no-kill trap,” he said. “Put stinky food like salami or smelly cheese in it. If there’s anything alive down there it will probably go into the trap, and it won’t be able to get out. Then you can take it to the park or somewhere and let the critter out.”

Logan set the trap up in the basement in a dark corner. But during the night the furnace clanged like usual, and in the morning the trap was empty.

The same thing happened the next day, and the next. Finally Logan returned the trap to Barak. “I didn’t catch anything,” he said.

“Then there probably isn’t anything to catch,” Barak replied.

Logan went back to his web of ideas. He read “What’s new.” What was new was that they had just moved into the house. Looking at the big unfinished area, he saw lots of cartons piled around. A few were touching a furnace duct. “Maybe there’s a problem with the boxes touching the duct,” he thought. He lifted some small boxes and slid the larger ones until nothing touched it. Maybe tonight he’d finally get a good night’s sleep. He needed to. His teachers were beginning to notice that he was falling asleep in class, and his grades were slipping.

But that night, too, the furnace banged and clanged, waking Logan up several times. And now, not only was the noise making his heart pound, but his anger was making it even worse. He felt like kicking the furnace, or pounding it with a hammer.

He had no more ideas, and he had run out of patience. The fourth time the furnace clanged, Logan got out of bed and stumbled to the door of his room. He looked out into the unfinished part of the basement. A little light filtered into the room from a streetlight outside, but mostly the room was dark.

Suddenly he remembered something Ms. Fagenbein had explained. On Passover, she had said, traditional Jews never ate chametz—bread, cake, or anything made with regular flour. For the whole 8 days of Passover, instead they used matzah and stuff made with crushed matzah, like matzah balls.

She had said that in the past, and even in Orthodox communities today, the night before Passover people checked their houses carefully for chametz. They had some ridiculous custom of walking through the house with a candle that just lit a tiny bit of the room at one time. “They think that they can see things that they won’t notice with the room bright,” his teacher had said.

Ms. Fagenbein had scoffed, but Logan was out of ideas. Maybe this, strange as it sounded, was worth a try. After all, the Jews had looked for leavening in their houses that way for an awfully long time. Lots of Jews had won Nobel Prizes, too, and smarts could be handed down from parents to children. So those Jews who kept up this custom couldn’t be stupid. If they could find chametz with just the little light from a candle, Logan thought, maybe I can find the furnace problem.

But he wouldn’t use a candle. He grabbed the flashlight from the drawer of his nightstand, rubbed his eyes, slid his feet into his slippers, and turned on the flashlight.

First he found the place where the furnace filter went. He ran the flashlight beam over the duct on all sides, from the furnace to the ceiling. Nothing interrupted the smooth steel. Then he started with the duct that began at the top of the other side of the furnace. He shone the light on the damper and pushed it. It was solidly in its slot, the way the tech had explained it should be. Then he continued, checking all sides of the duct until he got to the place where several smaller ducts began. These were older pipes, not the shiny steel ducts closer to the furnace. They must have belonged to an older furnace. He chose one randomly and started checking the smooth pipe. Suddenly his light lit a bump. Looking carefully, he saw that on the back of the pipe, almost hidden from view, was a handle.

“Huh.” Logan stared. The handle looked funny. He went back to a damper on another pipe. This one was perpendicular to the pipe. He moved it so it was parallel to the pipe and felt it click into place. Then he turned it back the way he’d found it, and it clicked at the “all the way” point. But the hidden handle was at an angle. Maybe it was only part-way open. Should it be all the way open or all the way closed? And which should it be?

He thought about waking his father and asking him. But when he had awakened his parents because of the noise they’d been pretty unhappy—okay, worse than that—and he didn’t want to do that again.

What did he know about the house?

He squeezed his eyes shut and thought about everything he’d heard. Then he popped them open. The real estate agent had said the old owner had been there for over 50 years. In his last years, the old guy lived only on the main floor. Maybe this valve shut off heat to the upstairs. But now his family lived in the whole house. They needed heat upstairs. What should he do? Maybe tomorrow he’d ask his father what he thought.

Just then the furnace clanged again. Standing right next to the duct, the sound was so loud Logan jumped, almost dropping the flashlight. His heart pounded, but he suddenly felt strong. He turned the valve so the pointer was perpendicular, like it was on the other damper.

Then he climbed back into bed. He slept soundly for the rest of the night. The next night again he slept, and the next, and the next.

“Logan, you haven’t complained about the furnace in a few days,” said his mother. one morning. “You’ve gotten used to it?”

“I,” he started. Then he stopped. His folks probably wouldn’t be happy to know he had been touching the furnace. They hadn’t really believed in the sounds, anyway. “I haven’t heard it. Maybe,” he replied, “I just got used to it.”

But in his heart he knew something else. That archaic custom of searching for leavened food with a candle had survived for generations because it was smart. In a brightly-lit room there was so much to see that the details kind of disappeared. In a dark room, though, when you had just a little light on one small place at a time, all the details of that little place jumped out at you.

He sat up taller. If that archaic custom made sense, today, it wasn’t archaic! Maybe other weird Jewish laws made sense, too. Those ancient Jews seemed to know what they were doing, and there might be other smart things he could learn from them. He would never again be so quick to call something foolish just because he didn’t understand it or because it was old.

Then he remembered his bar mitzvah. He was supposed to start preparing for it this summer, as soon as school was out. His buddies had said it was boring, but now it was looking like an adventure. He knew his parents weren’t interested in Judaism. The bar mitzvah was to please his grandparents. But now, he couldn’t wait to get started learning about the traditions of his ancestors. Smart old guys like them should be studied, he thought.

He took his cereal bowl to the sink, grabbed his backpack, and headed off for the day. Ms. Fagenbeim thought those ideas were archaic, but maybe that bearded Hebrew teacher, the one who always wore a yarmulke, would help him find some books. There was no time to start learning like now.

For Parents, Teachers and Others

Many years ago I lived for four years in a friend’s basement apartment. The furnace there made a racket and no one could figure out how to fix it. A new furnace repairman came the night before Passover. As he was tinkering, my landlord came down with a candle to do the hunt for chametz. The repairman was irritated, but the landlord insisted, and searched along all the ducts to see if there was any flour dust on them. Suddenly the half-hidden, half-closed damper came into view. The damper was opened wide, and the noises stopped.

Many old ideas that seem, from our 21st century eyes, to be out-dated and, by today’s standards stupid, turn out to be very relevant. These ideas include traditional morality—before sexual freedom became important, the number of intact, two-parent families was dramatically higher; depression, drug and alcohol usage among adults, and anxiety were also lower according to many studies. Discuss with your child/students other old-fashioned customs that still have relevance today: modest dress, respect for elders, a strong work ethic, etc. Getting kids to come up with ideas why old-fashioned concepts were good, rather than just telling them, can stretch their imaginations, open their eyes, and maybe even teach you something.

If you are interested in trying matzah balls, my recipe appears at the end of this week’s adult essay, Passover Cleaning: Not Just Spring Cleaning, April 2, 2024.

Wonderful ❤️