My Unfriendly View of the Jewish Book Council

Lessons from a bookseller and author

November is Jewish Book Month, sponsored by the Jewish Book Council, a much-anticipated event in the liberal Jewish world. Not so much by me.

Long before the Internet made international selling easy, I established the first mail-order Jewish book-and-gift business in the USA, selling to customers who lived in small Jewish communities such as Paris, Tennessee, Hobbs, New Mexico, and Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.

With a M.Ed. in elementary education, I was especially interested in children’s books. I was an avid reader of the bi-monthly publication of the Jewish Book Council and subscribed for many years after closing my business.

For Jews, literacy has always been important. Text study of holy books is part of traditional Jewish observance. The smartest students in religious schools were sought after as matches for daughters of wealthy families. Forty years ago and more, the proportion of books purchased by Jews far exceeded our proportion of the general population. But during the four years I owned my business, I saw the number of Jewish-themed children’s books drop, replaced by books about Black children. Publishers appeared to publish the same percent of books about minority children, but now they divided these between Jews and Blacks. (I have wondered if that contributed to the shrinkage of the children’s book market: publishers were no longer targeting their largest children’s market.)

What does this have to do with the Jewish Book Council?

The Jewish Book Council ignored children’s literature. They ignored changes in the children’s book sector, including some that should have been implemented in our books.

Insisting on “authenticity,” Blacks quickly began objecting to using non-Black artists to illustrate their books. This call to action was based on the belief that books should be both mirrors and windows: mirrors that reflect back the minority child’s life, and windows that show the minority child’s culture to readers from other groups.

But illustrations in Jewish-themed books have rarely been done by Jewish artists, and this was problematic. Non-Jewish illustrators drew pictures of rooms they were familiar with. Shelves of books, common in Jewish living rooms, were missing, as were ritual objects found in most Jewish homes such as mezuzahs on doorposts, Sabbath candlesticks, and Chanukah candelabras on shelves. Illustrators with Irish names used faces with ski-jump noses, red hair, freckles and green eyes; those with Polish names used tall, thin, fair children, and so forth. None of these illustrations were short, stocky, and dark-complexioned like me or my Jewish friends and relatives. Forty years ago, when intermarriage was not yet common, Ashkenazi Jews—those of us whose ancestors lived for generations in central and eastern Europe—were clearly recognizable as Jews, or at the very least, as “other.” But we did not appear in books.

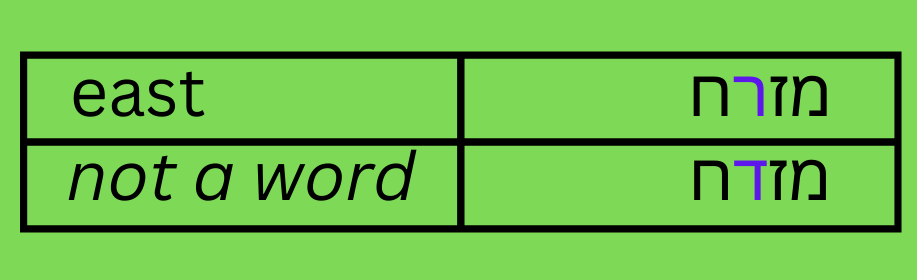

Faces were not the only problem; lack of understanding of anything Jewish was another. Best-selling author Jane Yolen’s book, And Twelve Chinese Acrobats, includes a picture with a mizrach, a wall decoration identifying the east toward which Jews pray. The only problem was that the illustrator confused two Hebrew letters so that the picture said mizdach, which is not a word, instead of mizrach (east). The letters are similar, but the error is immediately obvious to anyone who prays in Hebrew. How many children in Hebrew school felt stupid when they couldn’t read a basic Hebrew word?

At least one Passover book featured a seder table with braided Sabbath loaves as well as a plate of flat matzos. On Passover, often called “Holiday of Matzos,” bread is forbidden.

Another issue was that books with any religious Jewish information were considered “religious” and forbidden in school libraries because of the church-and-state issue—although books often mentioned Christian customs and now include lots of information about Islam and the Hindu religion. The Jewish Book Council should have been involved in convincing publishers and librarians that providing enough information about Jewish holidays and belief to make stories understandable was in no way forcing religion on anyone, it was merely making Jewish life—the “windows” part of multiculturalism—comprehensible to others. But no; the JBC remained silent.

Today, the strident voices of wokeism have meant that Jewish children’s books are replete with LGBTQ+ children and illustrations are filled with Chinese, Black, Asian and Hispanic characters because of the large proportion of liberal Jews who have intermarried. In fact, a few years ago when a self-published book had Ashkenazi-looking children in the pictures, the influential Facebook group Jewish Kidlit Mavens (with 1500 members) had a long and extremely ugly conversation about how the book was disrespectful to converts, and how Ashkenazis had been favored for years and it was now time for us to step aside for newcomers to Judaism.

A child assumes if it is published it is truth, and the illustrations in Jewish children’s books have been filled with lies for years.

Beginning when I was a bookseller I wrote to the JBC several times asking that they follow the lead of Black authors on issues of authenticity. Since editors were accomodating Blacks, they probably would have listened to Jews as well. But the JBC did not even trouble to reply to my letters. The Jewish Book Council has never been interested in truth in Jewish children’s books.

I have too many other issues with the JBC to go into here. I doubt that any children’s books promoted by the Jewish Book Council will include any meaningful Jewish values. Instead, I suspect they will satisfy the most left fringe Jews and alienate those children whose families try to provide some traditional Jewish content and values. Luckily, Orthodox parents generally restrict their purchase of Jewish-themed books to ones published by Orthodox publishers. But other Jewish children are being cheated of learning about their heritage.

And for this, the Jewish Book Council and its biggest annual event, Jewish Book Month, carry more than a little blame.

I’d love to get your recommendations on good children’s literature.

Worldwide. No doubt.