Exploring Textures

A nonfiction article especially for children ages 4-6, about 400 words long.

Humans have five senses: five ways we understand the world. These are hearing, seeing,

smelling, tasting, and touching.

This article is about using texture, especially felt through fingers, to learn about the world.

Fingers are wonderful things.

Babies suck their fingers,

hold their bottles,

and pick up fish crackers and bits of apple with them.

Children push toy trains on tracks,

stack blocks,

and cuddle dolls

with their fingers.

They pat the dog or cat

and pull their sister’s hair.

They hold books,

turn pages,

and punch keys on tablets, phones, and computers.

Fingers also feel.

Ice cubes feel very cold.

The stove can feel very hot. Keep away!!

There’s a big word for how things feel: texture.

Here are some words for different textures:

Bumpy

Coarse

Damp

Dry

Fleecy

Fluffy

Gritty

Hard

Lumpy

Rough

Sandy

Scratchy

Slick

Smooth

Soft

Sticky

Wet

Wooly

When we want to know which texture word fits something,

we don’t just poke, push, or touch it.

We stroke it.

That means to run our finger or fingers lightly over the thing,

The way you pet a dog or cat.

Or we can hold it between our thumb and fingers,

and stroke it. This is a good way to feel texture

in floppy things like fabric (cloth), paper,

or the rubber shelf liner I use in this video.

If we push down hard

or squeeze our fingers and thumb together,

it’s difficult to feel texture.

And if we move our hand too fast,

it’s also difficult to feel texture.

We have to be gentle.

Feeling different textures

and learning the right names takes time.

When you practice feeling textures,

you are teaching your fingers to be sensitive.

Putting the right names to things

lets you understand more later,

when you hear or read these words.

Why bother learning?

People who sew, knit and crochet

need to have sensitive fingers

so that they can make beautiful

and useful things.

Carpenters who work with wood

need sensitive fingers.

Welders and machinists do, too.

Surgeons who stitch up cut fingers

or put together broken bones

need sensitive fingers.

So does the nurse

who draws blood out of your arm

and gives you shots.

Blind people who read Braille—

writing that is done with dots for people who cannot see—

need super-sensitive fingers.

What if you never do any of those things?

When your fingers are sensitive enough

to feel the differences between textures,

and when you can describe things using texture words,

the world is a richer, more interesting place.

For Parents, Teachers, and Others

Background

I once knew a man who said that he could not see the difference between tulips and daffodils. I said they were not at all the same. He said people had told him that, but he could not tell the difference, especially between yellow tulips and daffodils. He said there were never flowers in his home growing up and no one ever taught him about them, so he does not understand what to look for.

I understand this; I know that if a parent points to a robin and says, “See the bird,” points to a crow and says, “See the bird,” and points to a bluejay and says, “See the bird,” the child will recognize birds, but not know how to identify different ones. But the parent who says, “See the robin,” “See the crow,” “See the bluejay” is stimulating the child to use his or her eyes and brain to identify how they are different—size, shape, and color—and how they are the same—feathers, two legs, beaks, wings, tails.

I had a sewing school for about six years during which time I taught people from age 6 through 60 to sew using sewing machines. I was shocked to realize that many children do not understand the word “texture” and have no idea how to use their fingers to feel. It is very, very difficult to teach sewing or another craft to people whose fingers are insensitive and clumsy.

Texture is a big deal in many day care centers and preschools. Unfortunately, many children in these places are not given personal attention. Teachers teach kids by having them touch different samples and learn their names. Generally, kids poke and push the texture samples. But the nerves in the fingers, the parts that feel and identify textures, work best with light, slow movements and by moving across or through samples, not when poked or pushed hard.

Additionally, texture samples in preschool generally have no context. They may come in a box: identically-sized squares of cardboard or plastic with a smaller square of some material in the middle. Or children might glue bits of texture on pages above the texture’s name. To little children, this is a game like Candyland, fun for a few moments but utterly irrelevant to life.

Between preschools, daycare, electronic technology, and sports, children are rarely given the opportunity to use their hands in ways that we were created to do so. It is up to parents to ensure that their young children develop their physical senses.

Ideas for Helping Your children

In order to help your children develop sensitive fingers, bring texture into all kinds of conversations. When helping a child dress, for example, instead of just focusing on color (do you want to wear the yellow shirt?) you can also say, “Do you want to wear the stretchy shirt? Do you want to wear the smooth shorts or the ones with bumpy fabric?

Do you have houseplants? African violets have velvety leaves; snakeplant has smooth, slick leaves; cacti are spiky. After introducing the different plants and the textures of their leaves until the children can identify them with their eyes open, blindfold them and let them try to identify them just with their fingers. They will be learning to truly notice the differences in plants as well as sensitizing their fingers. They will never be like the man who couldn’t tell a daffodil from a tulip.

When you are cooking, let them feel different ingredients. Does flour feel the same as salt? Do salt and sugar feel the same? What about ground spices and dried herbs? Messy? Yes—but that opens another lesson, cleaning up!

If you have children no younger than three years old, a box of old buttons can provide hours of educational play. (Sometimes you can find these at a thrift shop or at a yard sale, especially from the home of an elderly woman.) Children can sort buttons by size, by color, whether they have shanks or regular holes, or—relevant here—by the texture of the surface.

Ask your children questions about textures. Especially as children grow up, the world of science can open to them through these questions. For example, salt and sugar feel very similar. Looking at them through a magnifying glass, the particles look similar. They both have a crystalline form—they were dissolved and then dried as sharp-edged crystals. Flour, on the other hand, was a seed that was ground up. Its texture is not crystalline. White wheat flour feels soft and velvety.

If you bake gluten-free, you probably have several kinds of starch in the pantry: potato, corn, and tapioca are common. They all look alike and they all work about the same in food, but they have different textures. Cornstarch is soft and silky; potato starch has a coarse feel. (I have always used cornstarch instead of talc for comfort in the summer. Where I live in Israel, cornstarch is much more expensive than potato starch, so I once powdered on potato starch. It was scratchy.)

When you walk with your child—even a toddler in a stroller—instead of playing on your phone talk to your child about what you see. Stop often and let them feel the things you see: sticks and leaves, dirt, pebbles, stones, tree trunks. Learn the names of the plants and creatures you see. There are free and low-cost apps for your phone that make identification of things in the natural world easy. Being able to name things—robin, crow, bluejay; lilac, violet, azalea—makes the world feel friendlier and connects the child to the natural world.

By the way, texture is felt in the mouth as well as in the fingers. Once a child understands the concept of texture, you can use this when a child tries a new food and doesn’t like it. Ask if it is the flavor or the texture that they do not like. Eggs were a problem for me as a young child; I hated scrambled eggs because at home they were dry, and three-minute soft-boiled eggs were slimy. Fluffy scrambled eggs and 5-minute boiled ones were a revelation. You might get a child to enjoy a rejected food if you cook it longer or shorter, changing the texture.

Vocabulary

There are texture words that are most commonly used with things we feel with our mouths, words that describe how the surfaces of things look, and words that describe what our fingers (or other body parts) feel. Slick and shiny come to mind: shiny is how something looks, slick is how shiny often feels.

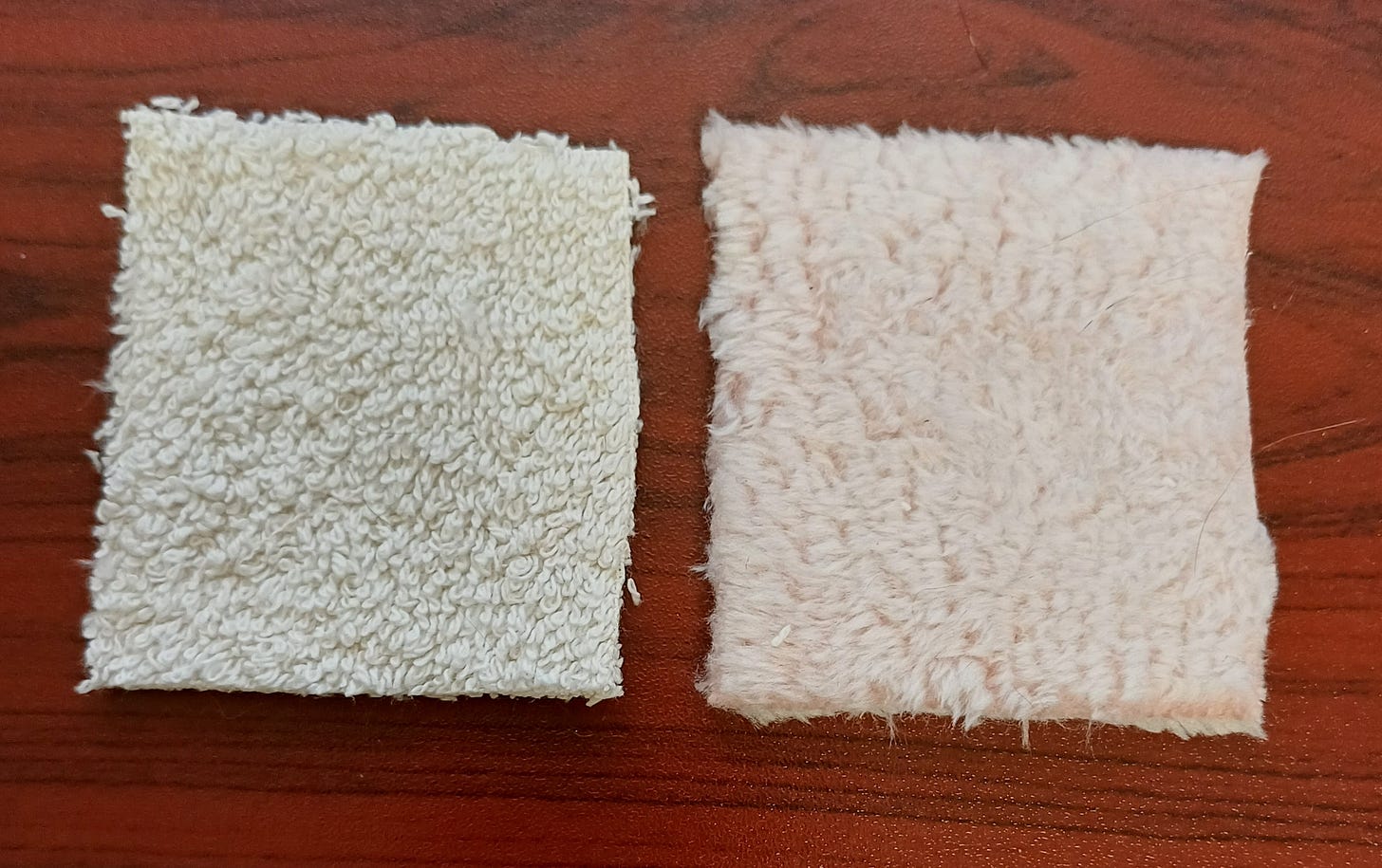

Two-dimensional pictures are not always helpful in determining texture These two samples look like they might feel the same, but they are very different. The creamy one is coarse cotton toweling; the pinkish one is soft, cuddly synthetic plush.

Here are some words that are often confused:

Bumps are smaller than lumps.

Grainy, gritty, and sandy: Grainy and gritty are textures made up of particles like sand. Sandy means covered in sand, such as bare feet at the beach. Note that the grain of wood is not a texture, it is light and dark lines from wood’s natural growth pattern, as seen on the table in the photo above.

Crispy is generally a texture felt by the mouth, not the fingers. Crisp fabric is stiff and has a more formal look than soft, flowy fabric.

Grooved and ribbed often look the same in pictures, but are opposite. Grooves are cut into a surface while ribs stand out from the surface.

Some texture vocabulary lists include words that are technically not textures. One list, for example, lists many different types of fabrics. The fabric types and products are not textures; I would have edited these words out of the list. If you start getting confused, don’t worry about it. This is a complex topic and there is no single correct list of words related to texture.

Shawn Manaher, founder and CEO of The Content Authority and author of Texture Words: 101+ Words Related to Texture,[i] writes, “The richness and diversity of texture-related vocabulary enable us to paint vivid pictures with words…”

While this is true for adults, for children the glory of learning about texture is that it enables them to experience the fascinating differences in our world. When done organically, as part of getting acquainted with the world, helping your child discover the world of touch can open their intellects as well as their senses. As a bonus, adding this dimension to your relationship adds richness to the time you spend with your children.

Now, go have fun exploring the world in this new way.

[i] https://thecontentauthority.com/blog/words-related-to-texture#piled

Well done